People of a certain age know the Bee Gees’ “Stayin' Alive” as the right rhythm track not just for John Travolta’s strut, but also for anyone doing hands-only CPR. But decades later, Gen Z says it’s time to do-not-resuscitate that song.

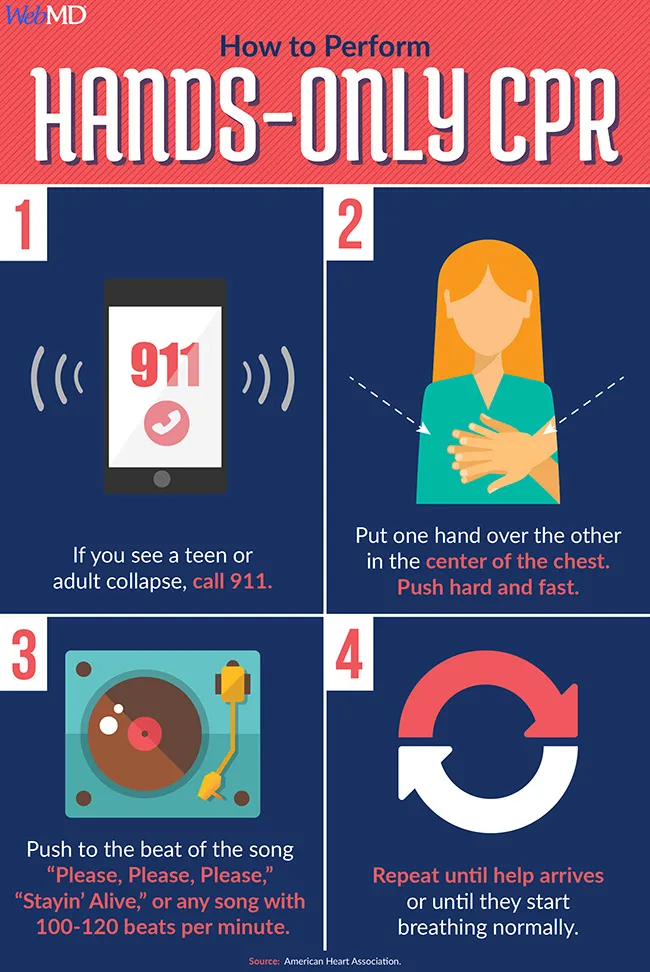

Once the gold-standard CPR anthem used in pretty much every training program, “Stayin’ Alive” may have boogied into its swan song era. Any tune with 100-120 beats per minute is fair game for doing chest compressions, according to the American Heart Association, but favorites among millennials, Gen Z, and Gen Alpha include Sabrina Carpenter’s “Please Please Please,” and “Espresso.”

There are even Spotify playlists dedicated to songs that fall into the correct CPR beat range, including everything from Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” to Billie Eilish’s “Birds of a Feather.”

“The point of all this is to make the process catchy enough that if someone goes down, a younger person can still render aid,” says Tiffany Moon, MD.

Moon, an anesthesiologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (and former cast member of the Real Housewives of Dallas, to boot), is usually the one at the head of the patient’s bed, calling the shots and guiding medical students and nursing staff on their compression technique when a person is coding. But she’s also performed CPR at church and on an airplane after someone collapsed.

“If you’re doing 2-inch-deep compressions to a song that's between 100 to 120 beats per minute, you’re probably doing a good job,” she says. “A better job, at least, than letting someone clutch their chest, collapse, and then call out for someone else to call 911.”

Likewise, the American Heart Association also wants people to know that if you see an adult in cardiac arrest, hands-only CPR – performing 2-inch-deep chest compressions at a rate of 100-120 beats per minute – is effective and relatively simple, even if you’re an untrained bystander. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., and stepping up to do CPR does save lives.

Moon says her goal with her TikTok video – set to Louis Theroux’s viral mini-rap, “My Money Don’t Jiggle Jiggle, It Folds” – is for people to learn that when someone collapses, you should start doing chest compressions right away. “Every minute that someone is down, their heart isn’t pumping blood to their brain, and they’re dying.”

Erin Mender, a 30-year-old registered nurse from Indiana, did just that in October 2024 at a University of Alabama football game.

She noticed that someone near her in the stadium was having a medical emergency. Kicking into gear, she started taking vitals and helping the EMTs get this person to an ambulance. Suddenly, one of the paramedics who had been helping during the first emergency collapsed.

Mender didn’t feel a pulse on the paramedic. She asked someone else to confirm that, and then started CPR. She says she’d done about eight codes – resuscitating a patient in a hospital setting – before that moment, but never out in public.

Despite the chaos in the football stadium, Mender says everything went oddly quiet, aside from a few key questions running through her head: “How much longer can I do these compressions for? Is someone getting help or an AED?” Eventually, her efforts revived the paramedic.

But if she didn’t have the innate medical training and nursing experience to perform compressions properly, Mender says that she would’ve been humming “Please Please Please” in her head to keep her on track.

It’s Normal to Be Physically and Emotionally Winded After Performing CPR

“It’s not a pretty sight if you see someone performing CPR,” Moon says. “I’ve had many medical students and nursing students be somewhat traumatized after their first code because it looks really aggressive.”

Mender, as seen in the video taken by a bystander, was wracked with emotion after she helped revive the EMT who had collapsed. On social media, a lot of people were confused why she had such a strong emotional reaction, but it’s common, even for experienced medical personnel.

“It’s not something that people outside medical settings see every day, nurses and medical personnel crying after codes,” Mender says. “It’s extremely emotional, but that shouldn’t deter anyone from jumping in and helping.”

On top of the whirlwind emotions, doing chest compressions is also physically demanding. You might be tired and sweaty afterward. If you feel yourself getting too exhausted, it helps to have another person waiting in the wings – ideally, with one of their own preferred CPR songs in mind – to jump in when you’re no longer able to keep going.

The ‘Heart Girl’ Goes From ‘Baby Shark’ to Charli XCX

By the time Aniston Barnette of Bristol, Tennessee, turned 16, she already knew several people who had died from cardiac events. A fellow student passed away after an accident during which no one around was CPR-certified. Her high school’s football coach died from a heart attack, and so did her grandpa.

Those losses led her to campaign for and eventually win the title of the American Heart Association's 2024 Teen of Impact. She raised funds for hands-only CPR education and encouraged many of her classmates to get certified.

Barnette, now 17, actually became CPR-certified in sixth grade. Back then, the earworm “Baby Shark” was all the rage, clocking in at 115 beats per minute – perfectly timed for compressions. She has since gotten retrained but has grown out of using “Baby Shark” as a musical touchstone.

Barnette has never had to do CPR outside of a training environment, but she knows exactly what song she’d use to guide her compression beats: Charli XCX’s “360.” The Brat album, she says, was a staple in all of her 2024 summer playlists, and with 120 beats per minute, "360" is American Heart Association-approved for hands-only CPR bop.

Social media has been the best tool to get the word out to teens beyond her small town, Barnette says. Her reach online is far greater than if she spread awareness only through word-of-mouth, and she encourages her peers to do the same.

“A lot of people in my town know me as the heart girl, but that’s OK,” she says. “I just want people to know that CPR saves lives, and hands-only CPR is such an important skill to have. I’m excited to see what the next generations do for heart health education.”